Bill Belichick’s first season at UNC didn’t lack for storylines. Before the year even started, his staff was openly suggesting that Chapel Hill would become the 33rd NFL team.

By midseason, buyout rumors were so widespread that Belichick had to clarify—twice—that he had no intention of leaving. And after a few high-profile losses, national pundits seemed more than ready to critique every incomplete pass and sideline expression.

The narrative was loud, and the internet was louder.

So, for this Domo on Data, instead of reliving all the speculation, I wanted to see what the data actually said. Because Belichick’s coaching history is long enough—and patterned enough—to put Year One at UNC in perspective.

Welcome to Chapel Hill: Why Belichick joined UNC

When UNC parted ways with longtime head coach Mack Brown in 2024, the university seemed to signal it wanted total transformation. Belichick represented that in the boldest way possible: six Super Bowls, decades of innovation, and a coaching tree that spans multiple eras of the NFL.

In the early months, optimism came easily. Talk around the program framed the hire as a turning point—an investment in discipline, structure, and a shot at becoming a serious football school on the national stage.

What followed was a disappointing season that didn’t match the hype, but it does resemble the historical pattern of his previous coaching arcs.

What the data says about Belichick’s first year

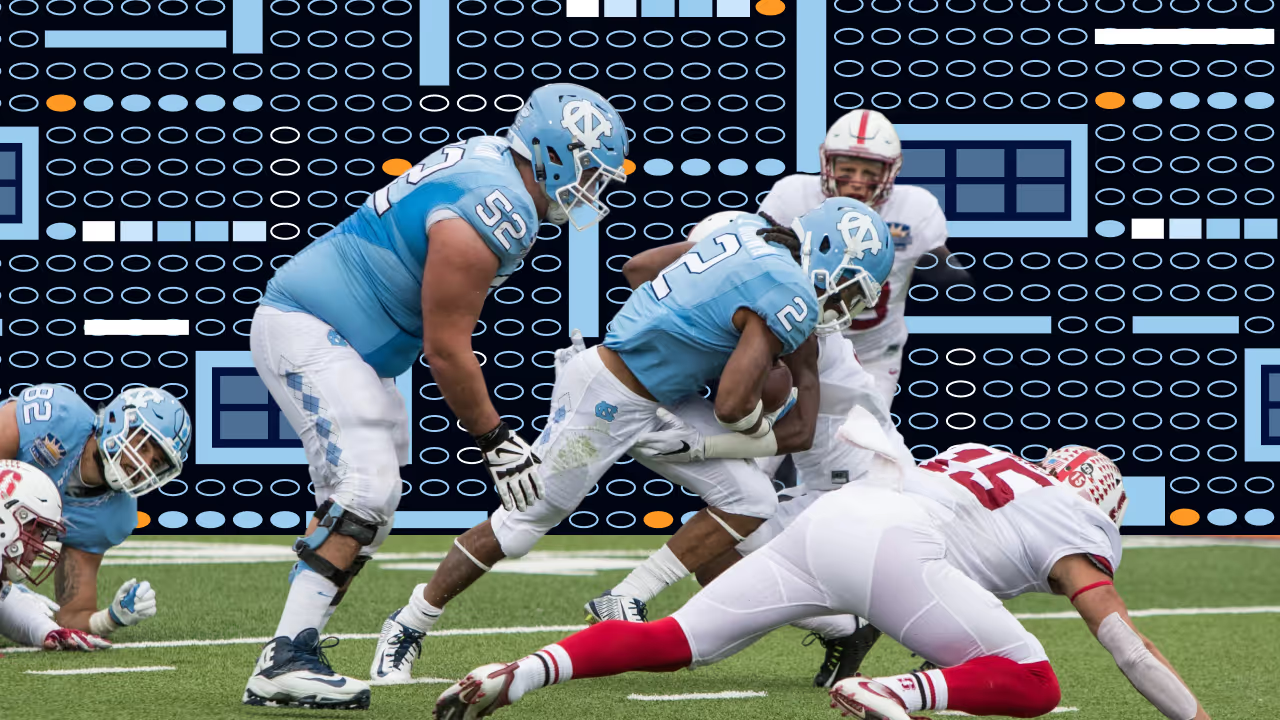

UNC finished the season with four wins and eight losses (4–8), missing a bowl game and adding another rivalry loss to NC State—the Tar Heels’ fifth straight. On its own, that’s a disappointing result for a program that invested heavily in a new direction. But when you line up his first seasons across all three head-coaching stints, similarities appear.

A. Year One performance and overall trendlines

Belichick’s Year One records:

- Cleveland: 6–10

- New England: 5–11

- UNC: 4–8

Different leagues, eras, and rosters, but the same early slope: uneven performance, flashes of potential, and clear signs of a system still being installed.

Historically, Belichick’s rebuilds don’t hinge on the first season; they tend to hinge on the second and third. (Of course, this is a sample size of only three, so we can’t say with certainty.)

In Cleveland, the Browns didn’t break through until Year Three, reaching 11–5 and making the playoffs. In New England, the transformation came even faster: a leap from 5–11 to 11–5 in Year Two, followed by multiple seasons with elite win percentages. Those jumps coincided with the roster aligning with the system and getting the right talent in place.

That context matters. UNC’s 4–8 doesn’t look good, but it fits closely with the front end of a coaching arc that has shown much steeper upward movement once stabilized.

B. How long it’s taken Belichick teams to gain momentum

Belichick’s stints at his two prior NFL teams followed a similar trajectory you can see in the data: a slow first year, incremental improvement in Year Two, and significant upside only after the system and roster match.

At the Browns, that window was brief. Belichick posted one standout season in 1994, reaching the playoffs, before a regression year in 1995 that ultimately led to his exit.

New England told a different story. After a 5–11 start in his first season, the Patriots made a dramatic leap in Year Two, jumping to 11–5 and beginning a run of sustained success. The shift aligned with Tom Brady becoming the starting quarterback, marking the moment when Belichick’s system and roster finally clicked.

Together, his previous stops point to a familiar pattern: early volatility, followed by measurable improvement once the pieces fit.

C. How Belichick compares to other UNC coaches so far

When you compare Belichick to UNC coaches across history, the data is blunt. His win percentage lands around 40 percent, which places him near the bottom of the chart—just behind John Bunting and well below the stronger eras under Mack Brown and Larry Fedora. (And for fans, the Fedora years…well, not exactly a high point.)

It’s a tough number at first glance, but worth remembering that almost every coach ahead of him had multiple seasons to build out their record. With just one season on the books, Belichick’s UNC performance is more of a snapshot than a verdict.

D. What we can and can’t conclude from this data set

But based on the data we do have, the picture becomes clearer: UNC fans weren’t wrong to expect a miracle. They were just sold the wrong timeline. What the school promised felt like an overnight transformation. What they actually hired, if history is any indication, is a slow, methodical, multi-year rebuild. Belichick’s first seasons in Cleveland and New England followed the same pattern: rough openings, gradual improvement, and real upside only once the roster, system, and staff finally clicked.

So UNC’s 4–8 debut under Belichick doesn’t look like a historical anomaly. It fits right in with the slow starts we’ve seen from his past teams. This season was the beginning of a coaching arc that tends to take time—and assuming he stays long enough, history suggests that the real story won’t reveal itself until Years Two and Three.

What’s next for Belichick in college football?

The next chapter will matter more than the first. If Belichick’s past holds, Year Two will reveal whether the system is taking hold and whether the roster can grow into it. But college football adds variables that don’t exist in the NFL: recruiting cycles, NIL structures, and rapid roster turnover.

Belichick has rebuilt teams before in the NFL. The open question is how well that approach translates to rebuilding a college program.

To explore the numbers for yourself—including comparisons across eras, trendlines, and coaching histories—check out the full app, including our affectionately named “Bilters” (read: filters). It frames the season in a way the headlines never could.