Se ahorraron cientos de horas de procesos manuales al predecir la audiencia de juegos al usar el motor de flujo de datos automatizado de Domo.

You likely have a long list—whether it’s of problems to solve, bills to pay, or features to build—but you have limited time and resources to address them. This is the universal challenge of project management and business analysis. How do you decide where to focus your efforts for maximum impact?

The answer often lies in the Pareto principle, commonly known as the 80/20 rule. This principle suggests that roughly 80 percent of consequences come from just 20 percent of causes. In a business context, this might mean 80 percent of your sales come from 20 percent of your clients, or 80 percent of customer complaints arise from just 20 percent of your software bugs.

To visualize this phenomenon and make data-driven decisions, analysts use a specific tool called the Pareto chart. It is designed to highlight the most important factors in a data set so you can prioritize effectively.

In this guide, we will explore exactly what a Pareto chart is, why it is a critical tool for quality control and business intelligence, and how you can build one that tells a compelling story. We will cover the mechanics of the chart, best practices for design and the potential pitfalls to avoid.

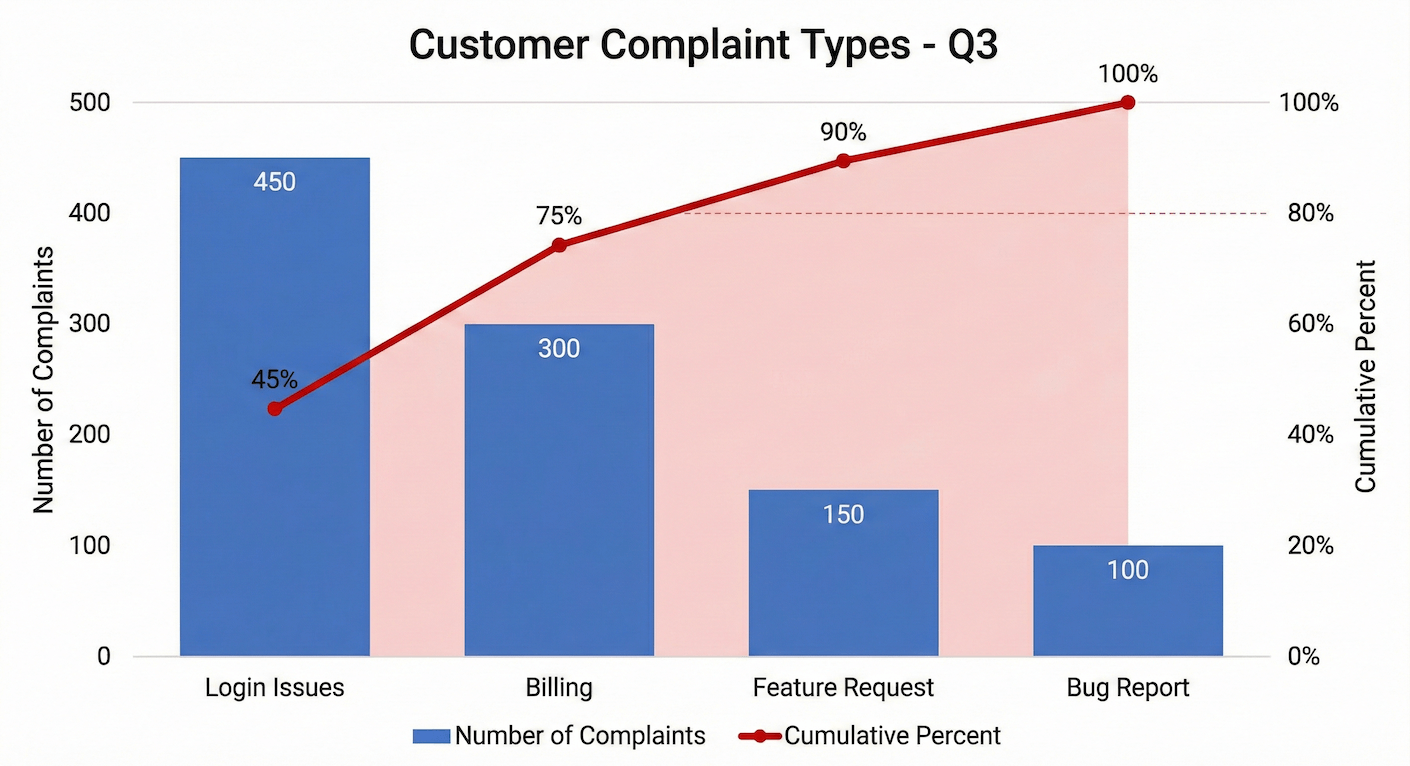

A Pareto chart is a specific type of chart that contains both bars and a line graph. It arranges individual values in descending order using bars, while a curved line travels across the chart to represent the cumulative total of those values.

The primary purpose of this chart is to highlight the most significant factors among a typically large set of factors. In quality control, for example, it often represents the most common sources of defects, the highest occurring type of defect, or the most frequent reasons for customer complaints.

The chart gets its name from Vilfredo Pareto, an Italian economist. In the late 19th century, he observed that approximately 80 percent of the land in Italy was owned by only 20 percent of the population. He later observed similar patterns with the peapods in his garden, noticing that the majority of peas were produced by a minority of the pods.

Later, management consultant Joseph Juran applied this concept to quality control and named it after Pareto. Juran’s goal was to separate the “vital few” problems from the “trivial many.” A Pareto chart is the visual manifestation of this effort. It helps teams realize that fixing just two or three major issues can resolve the vast majority of their headaches.

At first glance, a Pareto chart looks like a standard bar chart combined with a line graph, but its structure is more rigid.

In a standard bar chart, you might order the categories alphabetically, chronologically or by any other logic that suits your narrative. In a Pareto chart, the order is strictly determined by the value of the categories. The bar with the highest count, cost, or frequency must always be on the far left. The bar with the lowest value is on the right.

Furthermore, a standard bar chart usually only shows the individual magnitude of each item. The Pareto chart adds the layer of cumulative percentage, which helps the viewer understand the aggregate impact of the top categories.

Knowing when to use a specific visualization is just as important as knowing how to build it. A Pareto chart is not a general-purpose tool. It is a prioritization tool.

You should reach for a Pareto chart when you need to analyze frequency or causes in a data set. Common scenarios include:

The primary benefit of this chart is focus. When teams face a long list of issues, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed or to start fixing the easiest problems first. However, the easiest problems are rarely the most impactful.

By visualizing the data, a Pareto chart provides a mathematical justification for resource allocation. It allows a manager to say, “We are going to ignore these seven minor issues for now and focus entirely on these top two, because fixing the top two will resolve 75 percent of our customer complaints.” It moves the conversation from opinion to fact.

A Pareto chart is not useful when your data does not have a clear variation in frequency. If you have 10 categories and they all occur at roughly the same rate, the bars will be flat, and the cumulative line will be a straight diagonal. In this case, the Pareto principle does not apply, and the chart will not offer any insight into prioritization.

It is also not suitable for continuous data that cannot be easily categorized, such as temperature readings over time, unless you first bin that data into ranges.

To create or interpret a Pareto chart correctly, you must understand the two main components: the bars and the cumulative percentage line.

The foundation of the chart is a frequency table. You list your categories (causes, products, defects) and count how many times each occurred or how much cost they incurred.

The most critical step in the mechanics of a Pareto chart is sorting. You must sort your data set in descending order of frequency or impact. The category with the highest value goes first; the category with the lowest goes last.

A defining feature of this chart is the use of two vertical axes:

The line graph is what makes the chart actionable by connecting points that represent the running total of the percentages.

For example, if your first category represents 40 percent of the total defects, the line starts at 40 percent. If the second category represents 25 percent of the total, the line moves up to 65 percent (40 plus 25) above the second bar.

This line allows you to read the chart and say, “The first three categories account for 80 percent of the total problem.”

While the standard structure is the most common, there are variations that provide different angles on your data.

This is the classic version described above. It uses simple frequency (counts) for the bars and cumulative percentage for the line. The standard version answers the question, “Which events happen the most often?”

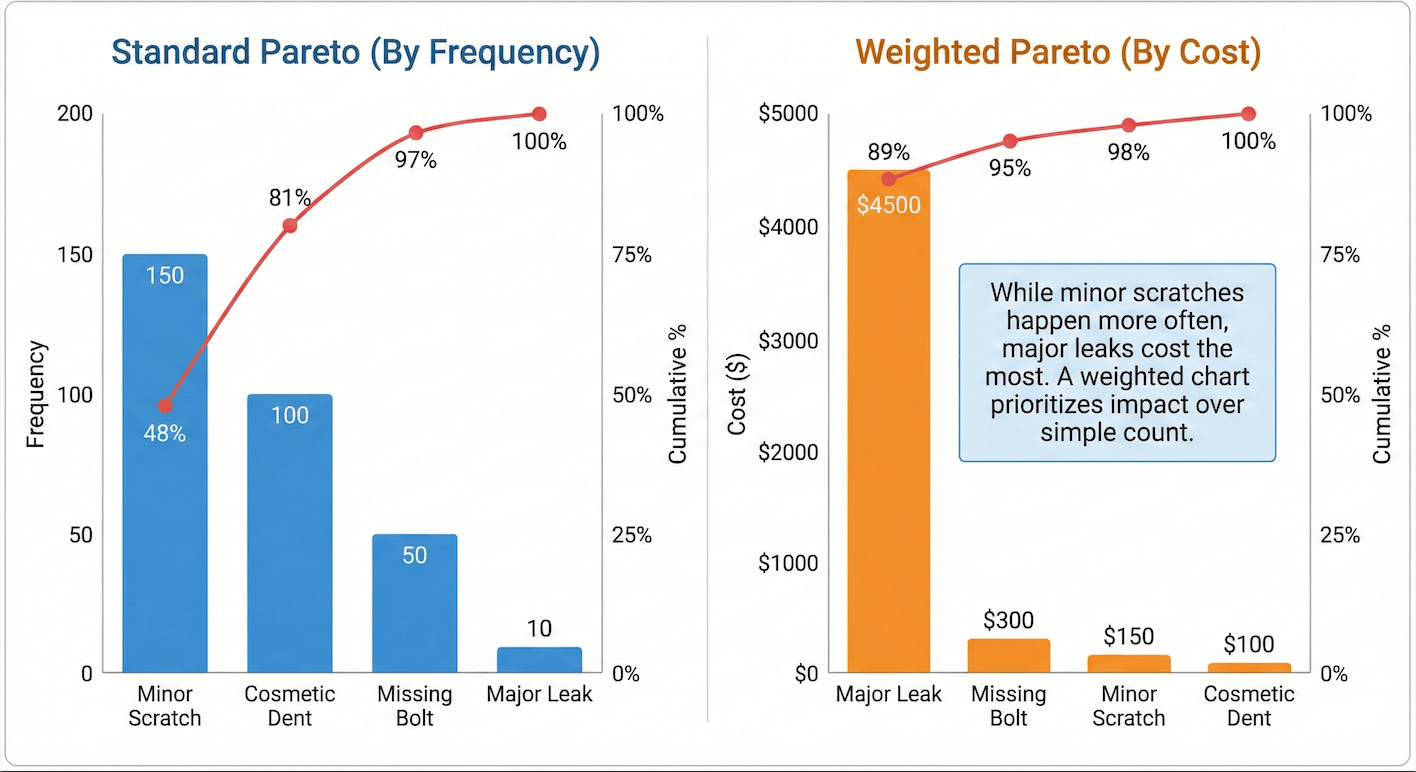

Sometimes, frequency does not equal impact. A minor defect might happen one hundred times but cost only one dollar to fix. A major defect might happen only five times but cost one thousand dollars to fix.

In a weighted Pareto chart, you modify the height of the bars to represent cost or impact rather than just frequency. This is often more useful for financial decision-making because it prioritizes money saved rather than just the number of errors fixed.

This variant involves placing two Pareto charts side by side. This is often done to show a “before and after” scenario. For instance, you might graph the defects in January, implement a fix for the top cause, and then graph the defects in February. This visual comparison confirms whether your intervention successfully reduced the impact of the “vital few.”

Even with good data, a poorly designed chart can lead to confusion. Because Pareto charts have two axes and two visual elements (bars and lines), they can easily become cluttered.

This cannot be overstated. If your bars are not sorted in descending order, you are not creating a Pareto chart; you are creating a confusing bar-line combination. The visual “stair step” down is essential for the reader to quickly grasp the ranking.

Because you have two vertical axes, clear labeling is mandatory. You should label the left axis with the specific metric (e.g., “Number of Defects” or “Revenue in Dollars”) and the right axis as “Cumulative Percent.” Without these labels, viewers may confuse the line values with the bar values.

Since the goal is often to identify the 80/20 split, it helps to add a visual reference. You can add a horizontal reference line at the 80 percent mark on the right axis. Where this line intersects with the cumulative curve indicates the “cutoff” point. Any category to the left of this intersection is part of the “vital few” that you should focus on.

In many data sets, you might have five major categories and thirty very small ones. Graphing all thirty small categories will make the chart unreadable and crowd the x-axis labels.

The best practice is to display the top five to nine categories individually and then group the remaining small categories into a single bar labeled “Other.” This “Other” bar should be placed at the very end, even if its total value is higher than some of the individual bars (though typically it is placed last to maintain the visual flow of the specific categories). This keeps the chart clean and focused on the actionable items.

Resist the urge to add too many gridlines. Since you have two different scales, gridlines from both axes can create a messy cross-hatch pattern. Usually, it’s best to show gridlines only for the primary axis (frequency) or to remove them entirely and simply label the tops of the bars.

To truly understand the power of this chart, let’s look at a few concrete examples of how they are used to tell a story.

Imagine a factory that produces smartphones. The quality assurance team logs defects for a month.

A SaaS company categorizes support tickets to reduce the burden on their agents.

When presenting a Pareto chart, do not just show the image. Guide the audience:

You do not need expensive software to build a Pareto chart. Most business intelligence tools handle them natively. Below, find the general process you can apply in any tool, from a simple spreadsheet to a complex dashboard.

This is the most important step. You cannot plug raw data directly into the chart. You must summarize it first.

Once your table is ready with columns for “Category,” “Value,” and “Cumulative Percent,” you can generate the chart.

After the basic chart is generated, apply the best practices mentioned earlier. Ensure the bars are touching or have a small gap (Pareto charts often use wider bars than standard charts). Format the right-hand axis to end specifically at 100 percent so the line ends at the top right corner of the plot area. This makes the visualization cleaner and easier to read.

If you are building this in a BI tool, add interactivity. Allow users to filter the data by date range or region. When a user filters, the Pareto chart should dynamically recalculate and re-sort. This allows a user to see if the top defect in “North America” is different from the top defect in “Europe.”

While powerful, the Pareto chart is not a magic bullet. There are times when it can mislead or oversimplify a situation.

The chart treats every category as independent, but in reality, causes are often linked. For example, if “Software Freeze” and “Data Loss” are two separate categories, the chart separates them. However, if the freeze causes the data loss, fixing the freeze fixes both. The chart does not show this causal relationship; it only shows the count.

Sometimes, there is no “vital few.” If you have a data set where the top category is five percent, the second is four percent, and the third is four percent, the bar chart will look like a flat staircase. The cumulative line will rise slowly and steadily. In this case, the Pareto principle does not apply. You are dealing with a broad distribution of issues, and a Pareto chart will not tell you where to focus because no single area dominates.

In a data-rich world, the ability to prioritize is a competitive advantage. More than a bar graph, the Pareto chart is a strategic framework for decision-making. By rigorously separating the significant few from the trivial many, it allows teams to work smarter, not harder.

To recap, successful use of a Pareto chart involves:

Whether you are improving software quality, streamlining a supply chain or optimizing a sales strategy, the Pareto chart remains one of the most effective tools for cutting through the noise and focusing on what truly matters.

The cumulative line represents the running total of percentages of all categories up to that point. It answers the question, “What percentage of the total defects are accounted for by this category and all the categories larger than it?”

Ordering is essential to visualize the drop-off in significance. It allows the viewer to instantly see the most important factors on the left. If they were unordered, the cumulative line would be jagged and meaningless, and the “vital few” would be scattered across the chart.

Yes. While often used for defects, they are excellent for sales analysis. They can show which products, customers or salespeople generate the majority of revenue.

The 80/20 rule is a guideline that suggests 80 percent of effects come from 20 percent of causes. On the chart, you often look for the point where the cumulative line crosses 80 percent. The bars to the left of that point are the “20 percent” of causes you should focus on.

They are excellent for dashboards because they provide "at a glance" prioritization. A manager can look at the dashboard and immediately know which three issues require their team's attention this week.